Saw Sean and Chris and Richard talking about incorporating setting details into player-facing components of the game that actually matter. Like, how do you do that thing that Dark Souls does that everybody loves so much but in a tabletop game? It’s easy to think of examples (there were three genius blacksmiths with unique styles and all magic swords worth anything visibly conform to one of the three, and each of a particular affinity for an alignment or whatever; in some dungeon there’s a bas relief of the Nightingale Demon being stabbed by the Rowan Angel and now players can guess that nightingale monsters take extra damage from rowan weapons etc etc), but I think grabbing it’s very easy to spit out these examples en masse but harder to relate them to each other in a meaningful way or to build a setting from the ground up around the player being able to form compelling interpretations of the world.

I think situational game design is actually a handy tool for solving this problem. Situational game design is a generally useful framework that is very useful for thinking about games in general and tabletop games in particular. It’s informed a lot of the game prep and writing I’ve been doing recently, and I think it would be very helpful for tabletop game designers at large. It’s not necessarily a perfectly total ideology of play, but it has helped me ask interesting questions and generate useful answers. The rundown I am going to give is extremely brief, and if you can get your hands on the book I’d really recommend it. Anyway.

Situational Game Design In Brief

Situational Game Design is a book by Brian Upton that proposes a methodology for designing and understanding games. Brian Upton is a video game developer, but the book addresses games of all kinds, and I think it can be usefully applied to tabletop roleplaying games.

Situational design centers the player and pays special attention to play that takes place when the player isn’t interacting with the game or isn’t trying to win the game. To be clear, situational game design takes non-interaction and non-pursuit of victory into account, but it does not ignore other aspects or forms of play. This more expansive attitude towards play is useful when thinking about rpgs. Most popular rpgs don’t have game-terminating win conditions, and a lot of enjoyment players derive from them aren’t strictly manipulating figures on the board, or even agents in a narrative. As Upton says,

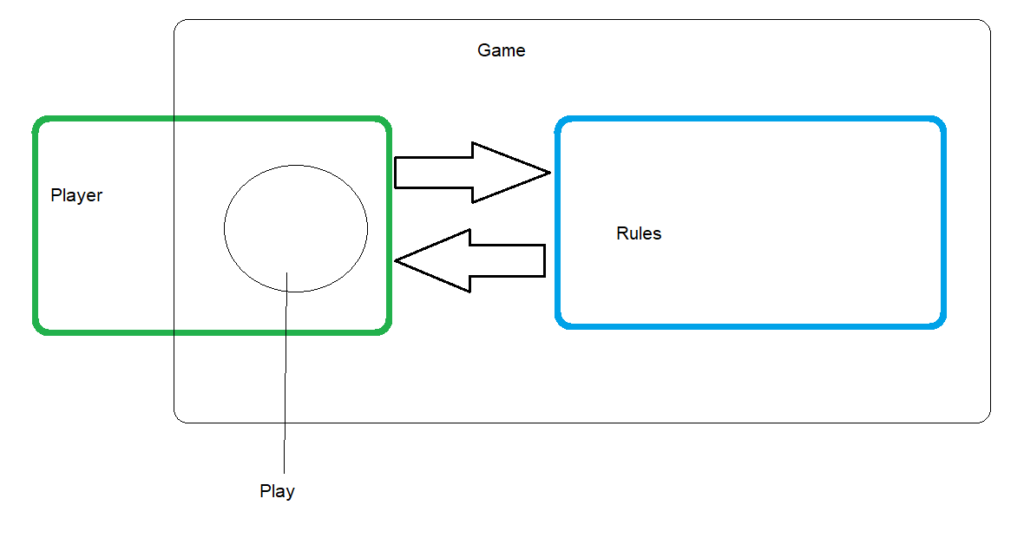

In situational design, the nexus of play lies not in the interface between the player and the game, but inside the player’s mind (Figure 1.2). Some of the moves the player makes will affect the external state of the game, but others will affect their internal understanding of the game, or even their understanding of themselves and the world at large.

pg 6

I have miserably reproduced figure 1.2 below

Things encapsulated by this definition of play that might escape our intuition or other formal definitions: making notes on character sheets about in-game events, naming an adopted pet, deciding you don’t like the Baron’s mustachioed butler, realizing that the Baron has been replaced by a simulacrum, perversely selecting Stone to Flesh instead of Flesh to Stone as your spell for this level, choosing on how to deal with your rebellious retainer after everyone has packed up and you’re driving home from game night.

Vitally, these are just as much play, and just as important to the situational designer, as deciding which kobold to attack or electing to do something in the fiction that triggers a PbtA move. Situational design doesn’t really elevate certain kinds of play over others.

To full understand play in the sense of situational design, we need to look at three concepts Upton lays out: situations, constraints, and moves.

We will start with situations. Upton’s definition is simple.

A situation is an interval of play that contains a choice.

pg 11

This is any interval of play and any choice, as suggested by my examples of play above. Situations can happen rapidly or continuously; deciding to fire a rifle at the alien soldier with an ice gun vs the alien soldier with a flamethrower and then immediately being faced with a choice between fighting the survivor or ducking for cover, with a series of choices after that, is the sort of the think you might expect in a typical video game. Situations can also happen in clear sequence as in chess, where you might decide which piece of yours to move or which piece of your opponent’s to capture, and then face a new situation once they have taken their turn.

Upton has a lot more to say about situations (naturally enough, in a book titled Situational Game Design) but this is a brief gloss, so we’ll stop here.

The next element is constraints. Upton explains them as follows.

When we’re within a situation we’re offered a range of moves to choose from. The constraints that structure a situation determine which moves we’re allowed to make, and therefore what choices it offers us.

pg 12

Upton offers rules as the most obvious kinds of constraints: in baseball, you can’t keep swinging after your third strike; in chess, you win if you take your opponents king and pawns can’t move four spaces diagonally. They can also be physics (balls move a certain way through the air when struck) or simulations of such (you want to lead your shots against a fast target in an FPS, or you can’t move through representations of solid objects in a platformer). There are also “soft constraints”, things players won’t or shouldn’t do. I can move my king out into the open in chess as soon as possible in chess, but soft strategic constraints will generally prevent an experienced player from doing so. In tabletop games, you might theoretically be able to kick a puppy or steal from your party members, but many players have constraints around how they want to express themselves in the game.

A key distinction is active constraints and potential constraints. While it’s true that you get to walk to first base after your fourth ball, that doesn’t matter to a player on third, and it matters even less to a player sitting in the dugout (I know very little about baseball, so I’m not sure why I’m leaning on it so hard for examples here). Constraints switch from potential and active all of the time, which leads us to the final core piece of situational game design:

Moves, which Upton mentions in his explanation of constraints.

A move is anything that the player does to change the game’s active constraints.

pg 15

This is a big deal, because Upton means anything. One of the examples of a move that he provides is doing nothing in a video game; if the game continues to proceed and your active constraints change, then doing nothing is a move. It can of course mean moving 30 feet closer to the kobold or running to second base, but it can also include “coming to like the Duke’s imperious secretary”, or “beginning to suspect the King is a simulacra” or “discovering the Church of Light’s god is actually a huge bug”. As long as it changes the constraints on the players’ behavior (maybe we don’t trust the Photonic Pope anymore on account of that bug thing), it’s a move.

Upton calls these “interpretive moves” and elaborates on them below

When we make an interpretive move, we’re not changing the state of the game, we’re changing our attitude toward it.

What this means is that play is not limited to situations that offer choices between competing actions; it also occurs in situations that offer competing interpretations. “What should I do?” is a playful choice, but so are “What’s happening?” and, “What does this mean?” These interpretive moves may be directed towards the past (“What caused this?” or towards the future (“What’s going to happen?”). They can even be directed towards ourselves (“Who am I?” or “Why am I doing this?”). If properly structured, these internal interpretive choices can be just as playful as choices that change the game’s external state.

pg 22

This also means that play (as Upton defines it) is happening in all kinds of places–the aforementioned car ride home from a D&D game, during character creation, while you’re standing in the shower thinking about how to solve a puzzle. It also means that there’s not a clean delineation between the crispy crunchy mechanical parts of the game that traditionally get a lot of attention (Reaction rolls, combat, skill check) and the more ephemeral parts less traditionally mechanized in the old school scene (setting, lore, building relations with NPCs). It’s just moves, constraints, and situations structuring and flowing into one another; the move of determining the God of Light is a bug leads to the situations in which you fight him; once he extends his glistening ovipositor, you’re likely making interpretive moves about him even in the heat of combat.

Okay, so that was a lot of preamble, and a lot of it I think is a really exciting way to think about games, but this blog post is titled Situational Narrative Design in Tabletop Games, so let’s move on to that part.

The Narrative / Setting Stuff

So if we’re thinking about that initial problem: how do you write a setting that is well suited for players interpreting and thinking about? How do you write a setting that provides them information they can act on? I think a possible way is to structure it around interpretive moves.

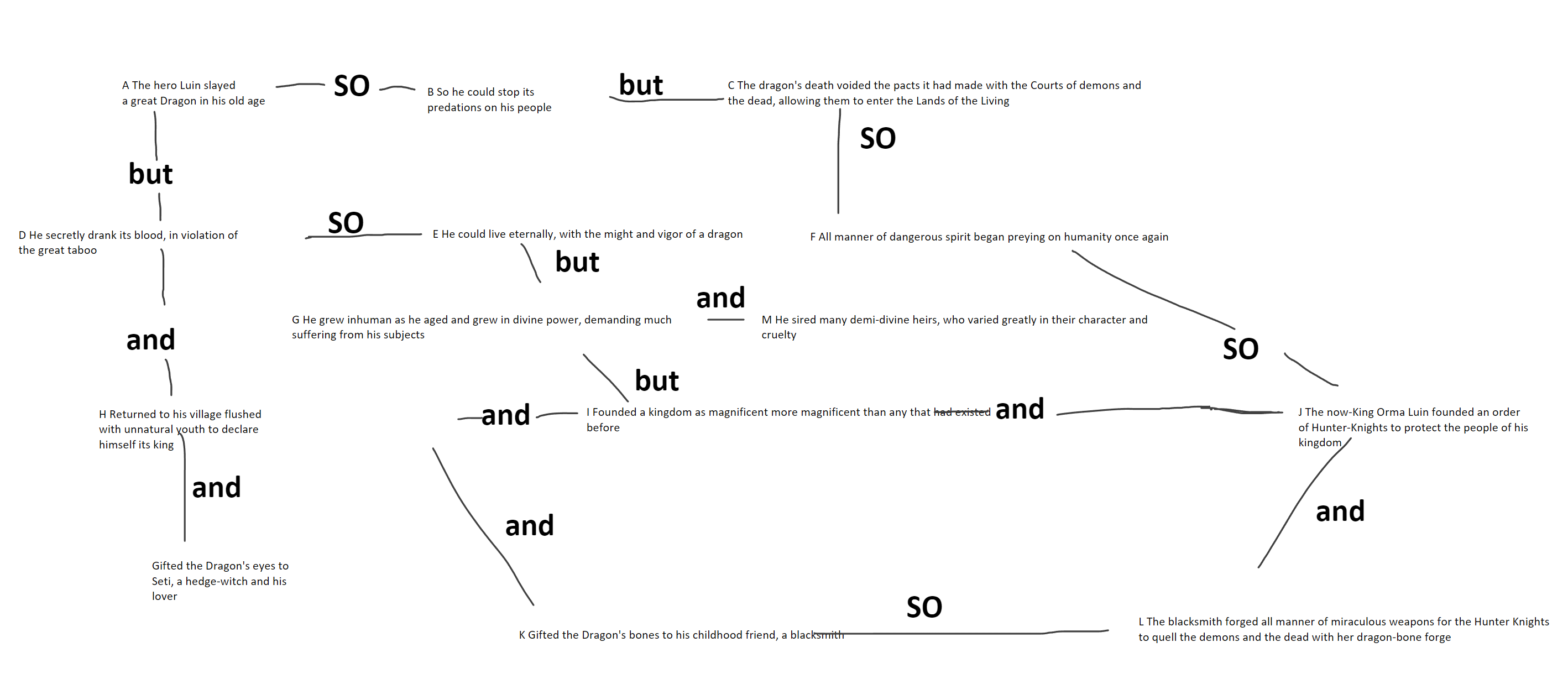

The way that I did this is sketch out a setting in terms of brief clauses and phrases linked with one of the following conjunctions:

- but: for two facts that exist in conflict with each other, either conceptually (The king said he did this BUT actually did this instead.) or in terms of actual forces (The Good Guy Army marched into the desert BUT the Bad Guy Army stopped them)

- so: for facts that have a causal relationship (The hunter killed the dragon SO it would stop preying on his people

- and: for facts that occur concurrently (He founded a Kingdom AND gave gifts to his new supports)

I included the rough Situation Map of this below. This isn’t complete and is a proof of concept; it’s also a setting I only had a rough idea about before I started. Each fact should be pretty interesting and important to the setting at large; you don’t have to be too granular about it. Also if I were to do this again, I would probably include arrows to show which direction the “so”s and “but”s are going but it’s fine I guess.

You’ll note that there are letters associated with each fact. I used these to cross-reference the facts with details in the setting; for each fact I tried to come up with a handful of ways that fact impacted the actual world in terms that players would notice, like so:

A The hero Luin slayed a great Dragon in his old age

- Everyone knows: Orma Luin, the divine Dragon King, founded the empire whose ruins we all live in.

- Many dungeons are his fortresses and palaces, which depict his victory over the monstrous and gluttonous Dragon

B So he could stop its predations on his people

- Even know, there are tracts of desert and scrub winding their way through forest and meadow, wastes where the dragon’s fiery breathe scorched even the fertility from the soil.

C The dragon’s death voided the pacts it had made with the Courts of demons and the dead, allowing them to enter the Lands of the Living

- Everyone believes: WIth its dying breath, the Dragon spitefully unleashed all manner of wicked spirit into the Lands of the Living

- Many dungeons are the haunts and shrines of the Demons and the Dead

- Many people out in the hinterlands swear fealty to a Greater Corpse or Demon rather than a human lord

D He secretly drank its blood, in violation of the great taboo

- Everyone knows: sorcerers drinking an animal’s blood is forbidden, as is magic that lets one assume their shape

- Most mayors or elders will offer significant bounties for the heads of nearby witches who violate the taboo

- Hunter Knights will go to great lengths to capture or kill witches

E He could live eternally, with the might and vigor of a dragon

- Everyone believes: The gods blessed Orma Luin with his youth and divinity for slaying the wicked Dragon.

- Orma Luin still nominally rules the ruins of his empire from his Isle Palace.

- Orma Luin is and was an army unto himself

F All manner of dangerous spirit began preying on humanity once again

- Hunter Knights and Clerics do the constant work of keeping humanity safe from Demons and the Dead

- Many dungeons are the haunts and shrines of the Demons and the Dead

- Many people out in the hinterlands swear fealty to a Greater Corpse or Demon rather than a human lord

- If you learn the lawful tongue of the Dead or the chaotic speech of the Demons, they will tell you all manner of things about Orma Luin that the Hunter Knights would kill you for repeating.

The full situation map key isn’t complete, but you get the idea (probably, I hope).

The next step is to go through the key and pull out things you need to put in your setting. What we have here includes

- Multiple dungeons that depict Orma Luin defeating a dragon

- Narrow, geographically improbable stretches of wasteland, scrub, and desert in otherwise fertile areas of the map

- Multiple dungeons themed around demons or the undead

- Remote settlements governed by demons or the dead

- Settlements that offer bounties for shapeshifting witches

- The ability for players to become shapeshifting witches (if they don’t mind the scrutiny of witch-hunters)

- Hunter Knights on encounter tables

- A really nasty dungeon with a really nasty Dragon King inside

- A couple locations that are old battlefields where the Dragon King wasted an army by himself

- Possible Hunter Knight class

- NPCs expecting clerics to help them hunt undead and demons

- Alignment languages let you learn things from the Dead and Demons

- Rumors, secrets, and lies Demons and the Dead will tell you, including and especially things that contradict the “everybody believes” entries in the key.

- And so on and so on.

That’s a pretty good list to go off of considering I’m working off of a half-finished proof of concept based on a setting I didn’t know much about when I started. The blacksmith entry would be the impetus for magic weapons in the setting, and their rarity would be tied to the fact that one demidivine blacksmith had to make them; they might all have her maker’s mark and be illegal to own and technically property of the Dragon King. The node about Seti (I believe item G) could give you insight into Clerics and Magic-users and how they’re trained and treated.

This process ensures that most things the players encounter tie back to the core narrative we mapped out at the start, while also not forcing them to think about it too much if they don’t want to. Since the conjunctions that link the nodes are implicit or unstated, players are allowed to use their own interpretations to interrelate pieces of information. For example, Node M (He sired many demi-divine heirs, who varied greatly in their character and cruelty) could yield grotesque pleasure-palaces belonging to princes and princesses as dungeons in setting. If players only encountered setting details associated with Orma Luin being a great king, they could decide if he was a noble person who had bad kids or if the apples didn’t fall very far from the tree.

Each node is sort of the foundation of an interpretive situation. The situation will vary player to player, and even playgroup to playgroup (assuming multiple people are playing the setting) because individual players bring their own assumptions and preferences, and different tables will naturally encounter the information in different orders.

Anyway, this has been a little meandering, but that’s all about I have for today– a possible way to make settings with capital letter Lore tie into player-facing elements of the game. If you can, read Situational Game Design; it’s great and Brian Upton explains it way better than I do here.

One thought on “Situational Narrative Design in Tabletop Games”

Comments are closed.