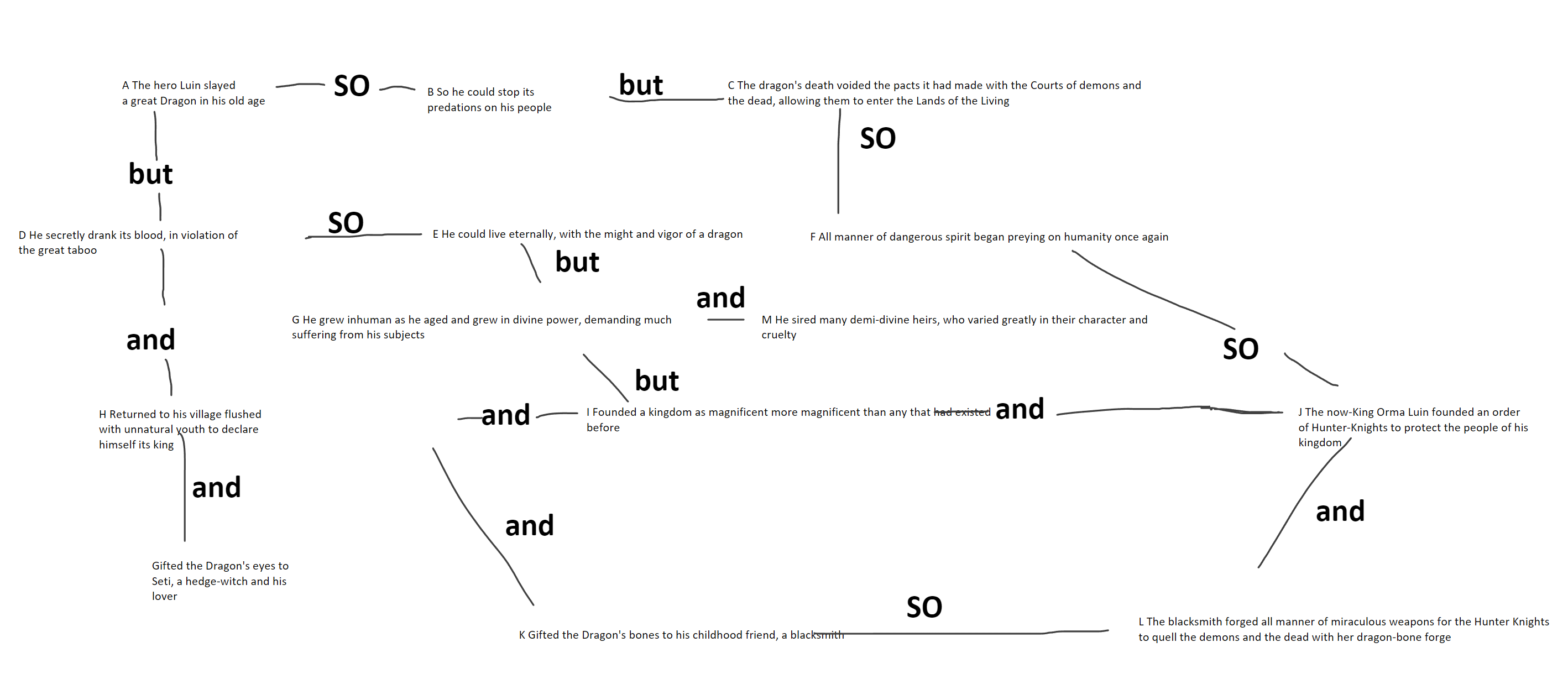

Watching Chainsaw Man, thinking about Alex’s discussion of designing adventures around spells (and the vagueness of OSE’s phantasmal force) and well as Deeper in the Game’s magic items and philosophy behind them.

These are two abilities PCs can pick up; I would consider putting them at the end of their own adventures, seeding them in as treasure, or making them the result of magic research. I would think they’d fit most into what characters can do around level 5 (the Snake can do 5d6 damage in a very similar manner to lightning bolt, plus a bunch of other mean bullshit, but only a very limited number of times). They also require the DM to commit to particular kinds of games (not being too wishy-washy about how much time has passed for the Snake, making sure that a looming threat of social violence eventually gets acted on). The Snake also assumed that enemies have 1d8-sized HD; it becomes too strong if HD are 1d6 (so just bump its damage die size down to d4, I guess)

I would also think about making these count against follower limits imposed by Charisma, since someone cutting creepy deals is offputting and it categorizes them as a social relationship mechanically.

You could also drop these in at level 1 as a DM if you were comfortable to running the kind of game where the consequences of how PCs solve problems really matters. If anything goes in the dungeon, then these are just strong and creepy (which is fine); if a bunch of scrubs punching a hole through the local dragon subjects them to all kinds of troublesome scrutiny, then these are much more interesting.

I don’t imagine the Snake or the Foxes as having much explanation in the world; they are cruel and unfamiliar things that have an unknowable interest in a particular PC.

The Snake

Congratulations. You have formed a contract with the Snake. You may sacrifice one of your fingernails to give it a single command. You do not know why the Snake wants your fingernails. It probably just enjoys hurting you.

Any time the Snake’s damage is mentioned, use 5d6. For each fingernail you give it, add +1 to the roll. For each creature it devours with more HD than it has damage dice, add 1d6 to the roll. For example, if you have given it 3 fingernails, its damage is 5d6+3. If it successfully devours a 7 HD wereboar, its damage increases to 6d6+3.

The Snake can only materialize in places within your line of sight and within earshot of your voice. The Snake materializes without fanfare or sound for the briefest moment to perform the acts you command before vanishing.

On your turn, you can command the Snake to do any of the following.

- Snake, strike. You can simply tell the Snake to attack. It can attack a single target, or all creatures in a 100’ by 5‘ line. The line can originate from any point in range and has the orientation of your choice. The attack deals the Snake’s damage, Save (vs Magic) to take half damage. If this attack deals more damage than ½ their maximum HP, they must Save (vs Magic) again or the attack will kill them instantly as the Snake carves a hole through their body.

- Snake, devour. You can tell the Snake to devour a single creature. This deals the Snake’s damage, Save (vs Magic) to take half damage. If this damage exceeds their maximum HP, the Snake successfully devours them, and can vomit them up as a separate favor. If this does not reduce the enemy to 0 HP, they stick in the Snake’s craw for a moment before it dematerializes. This annoys the Snake, and the next favor you ask of it requires an additional fingernail. It will tell you if it thinks it will not be able to devour a creature before it takes the fingernail.

- Snake, release. You can tell the Snake to vomit up an enemy it has devoured for you. This enemy has ½ their normal HP and 10 AC, but retains all other abilities and statistics and acts as your perfectly loyal follower. It dissolves into oily smoke when reduced to 0 HP or the fingernail you sacrificed for it finishes growing back.

- Snake, destroy. You can tell the Snake to obliterate a tube of solid, non-magical matter up to 100 ft in length and 5 ft in diameter. The tube can be in any shape or configuration (a cylinder, a spiral, a torus). The Snake obliterates this material by traveling through it; if it encounters a creature, it will deal its damage to them as if it had attacked and then immediately vanish (leaving the job of destroying the object or volume incomplete).

At any time you or an ally in range are about to take damage (after the attack is declared but before any dice are rolled)

- Snake, protect. You can tell the Snake to block the attack. Roll its damage, then deduct incoming damage by that amount. If it does not negate all damage, its physical body is destroyed, which it will spend many mortal lifetimes regenerating. It is in your best interest to be dead by then.

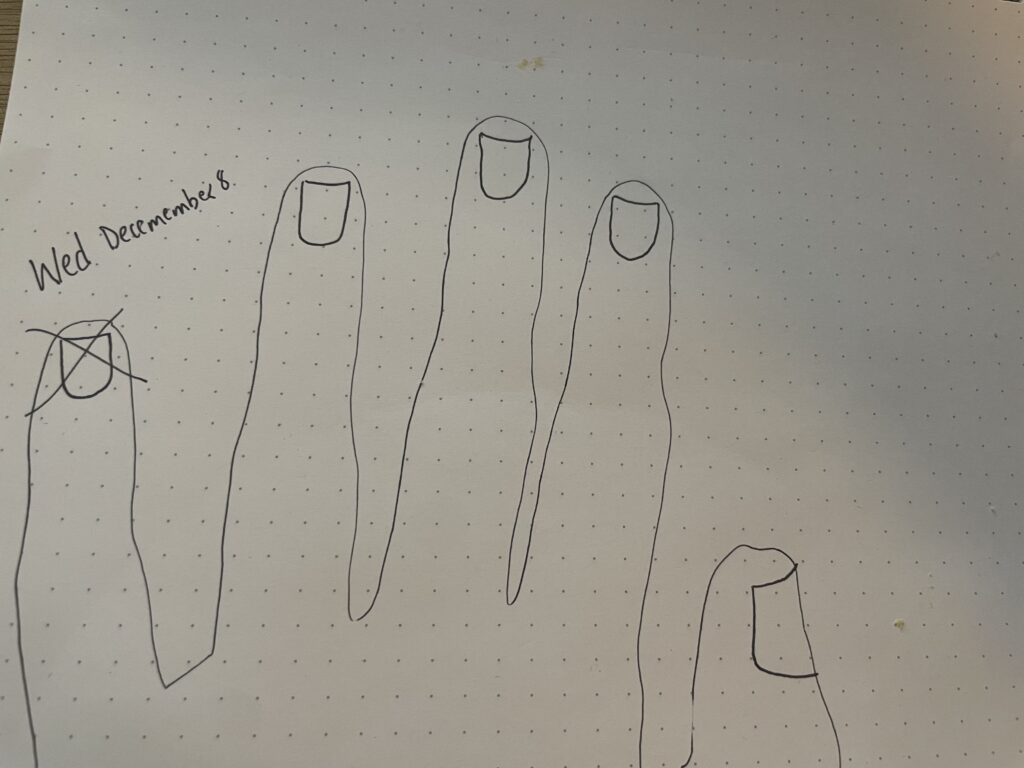

Fingernails

Trace your hands (or at least your fingers) on the back of your character sheet and draw on fingernails. Whenever you offer one to the Serpent, right the in-game date you used it, so it’s easy to remember you’re missing it (and also to make it easier to remember when it grows back)

Though it always hurts more than you expect when the Snake claims a fingernail, no matter how many times it happens, you find your reaction oddly muted: no desire to flinch or cringe or clutch your hand. The Snake is particular and precise, and so the wound is nearly nonexistent; there is minimal bleeding and no trauma to the tissue. The Snake simply makes you unwhole. This is also what it does when it attacks your enemies.

The Snake always leaves your nail matrix perfectly intact, so that you can grow more fingernails for it to claim. It takes six months in-game months for a fingernail to grow back. If your game has downtime turns where there is a change of a random event, six of those will do.

If you need to call the Snake and have no fingernails left, there is no cause for concern. Perhaps there is something else you could offer instead?

The Foxes

Oh dear. You have formed a contract with the Foxes. Decide how many out of the five of them you have made a contract with, here and now. For each one, someone in your future will tell you a disastrous and believable lie, even if it contradicts their own nature and they believe they have no reason to deceive you. Everyone has a reason now, and it is the Foxes.

You can now command any number of Foxes to create illusions. Assigning more Foxes to an illusion increases the number of people it can deceive and the number of senses it can manipulate. Targets of an illusion may make a Save (vs Magic) to avoid being deceived, with a penalty equal to the number of Foxes assigned to the illusion. On a successful Save, they realize something is pushing and pulling at their mind.

| No. of Foxes | No. of Targets |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | ~5 |

| 4 | ~10 |

| 5 | ~20 |

Foxes are fickle and lazy. When you create an illusion, roll 1d6 for each Fox you assign to its creation. For each die that comes up a 1-3, one of your Foxes loses interest in helping you until your next downtime, preventing you from commanding them until then.

The Foxes do not accompany you on your adventures. However, your shadow, reflection, and appearance to other in dreams sometimes seem to have yellow eyes, sharp teeth, or perhaps a bushy and poorly concealed tail.

Illusions

Illusions can deceive senses in any way you please. You can make a target perceive something that does not exist at all, like a person or a wall. Illusions can move and act, such as an illusory wave fluttering in the breeze or an illusory person conversing and moving around (though it’s just the Foxes acting behind the scenes, of course).

You can also alter perception: wholly occlude someone’s vision, make an ally in their sight look like someone else, or prevent them from perceiving a particular person or object. You can also do something like make someone’s voice sound higher or lower, or make it sound like everything they say is an insult.

Illusions exist purely in the perception of their targets, but are shared amongst targets; an illusion brings a single, attenuated reality into being for those its deceives. For example, if one illusion affects two enemies, they must both perceive the same event unfolding. You could not make one enemy see an illusory dragon and the other see an illusory tree. You could create an illusion that depicts both or either, however. You could also set two groups of Foxes on two different illusions, though this would take more rounds if you are in combat and the individual illusions would not be able to deceive as many senses.

You can give false solidity to an illusion with the sense of touch. This does not allow illusions to support weight. For example, the victim of an illusion can’t walk through an illusory wall if the illusion deceives their sense of touch, but they would fall through illusory stairs. An illusory gale that includes the sense of touch would make its victim stumble and fall, but it could never lift them off the ground or propel them.

If an illusion ends up depicting something impossible (someone falls through solid-feeling illusory stairs, for example, or an illusory dragon picks them up with painful and powerful claws and then they are not actually lifted off the ground), the victim who witnesses the paradox may make a Save (vs Magic) to see overcome the illusion, thus losing all perception of it but experiencing stark reality once again. If they fail, they will confabulate the paradox away.

You can perceive your illusions and underlying reality simultaneously and without confusion. Illusions last until they wholly leave your perception.

Example

You have a contract with four of the Foxes, having decided five grievous lies in your life would be too many. You encounter a party of six goblins who seem like they might attack you. You command three of your foxes to deceive them with an illusion; you decide the illusion should impact sight, sound, and touch and affect five of the goblins. You tell three of your foxes to make it appear in the sight of five of the goblins that the sixth has drawn his weapon and attacked his fellow. The five deceived goblins see the sixth raise his club and strike; they feel the splatter of blood. The false target feels the impact of the club and the sound of it crunching his bones. The goblins gang up on the false attacker, and then begin brawling amongst themselves.