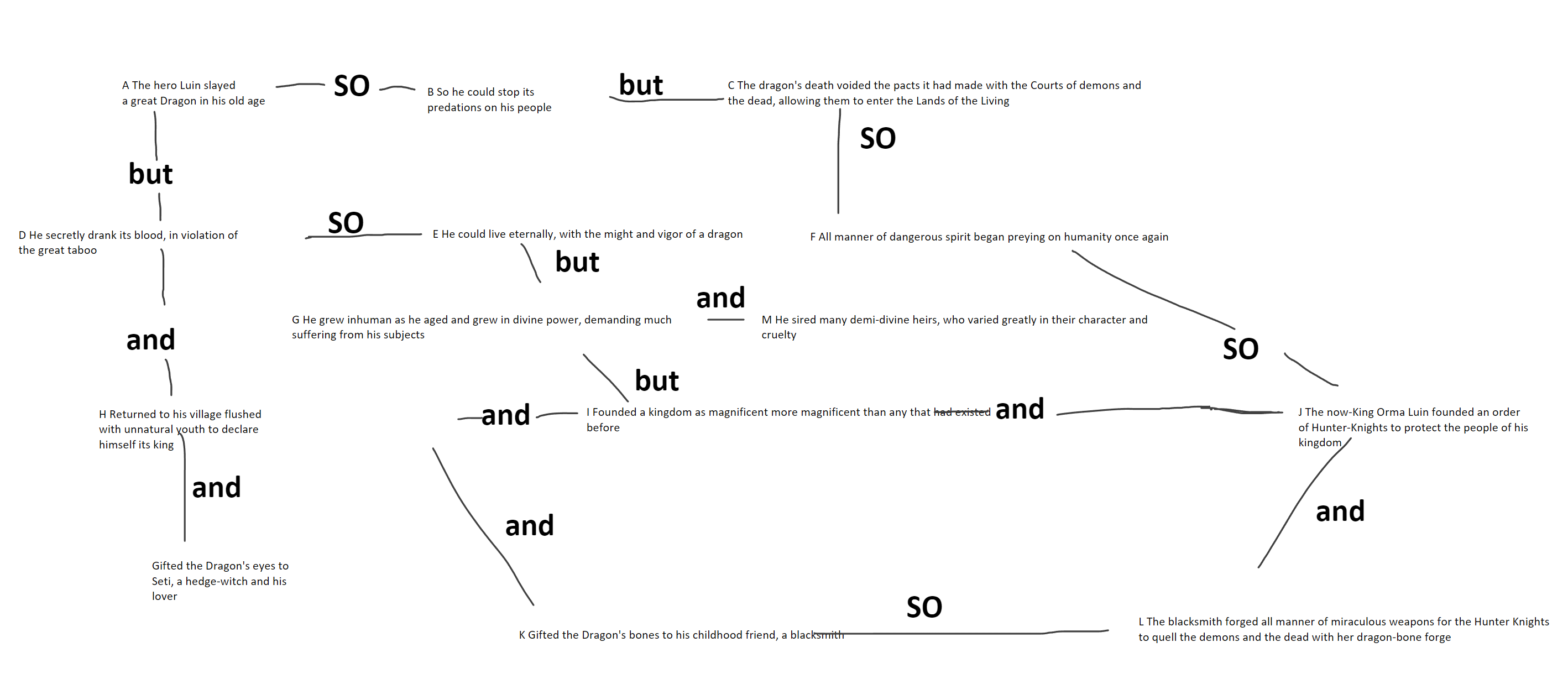

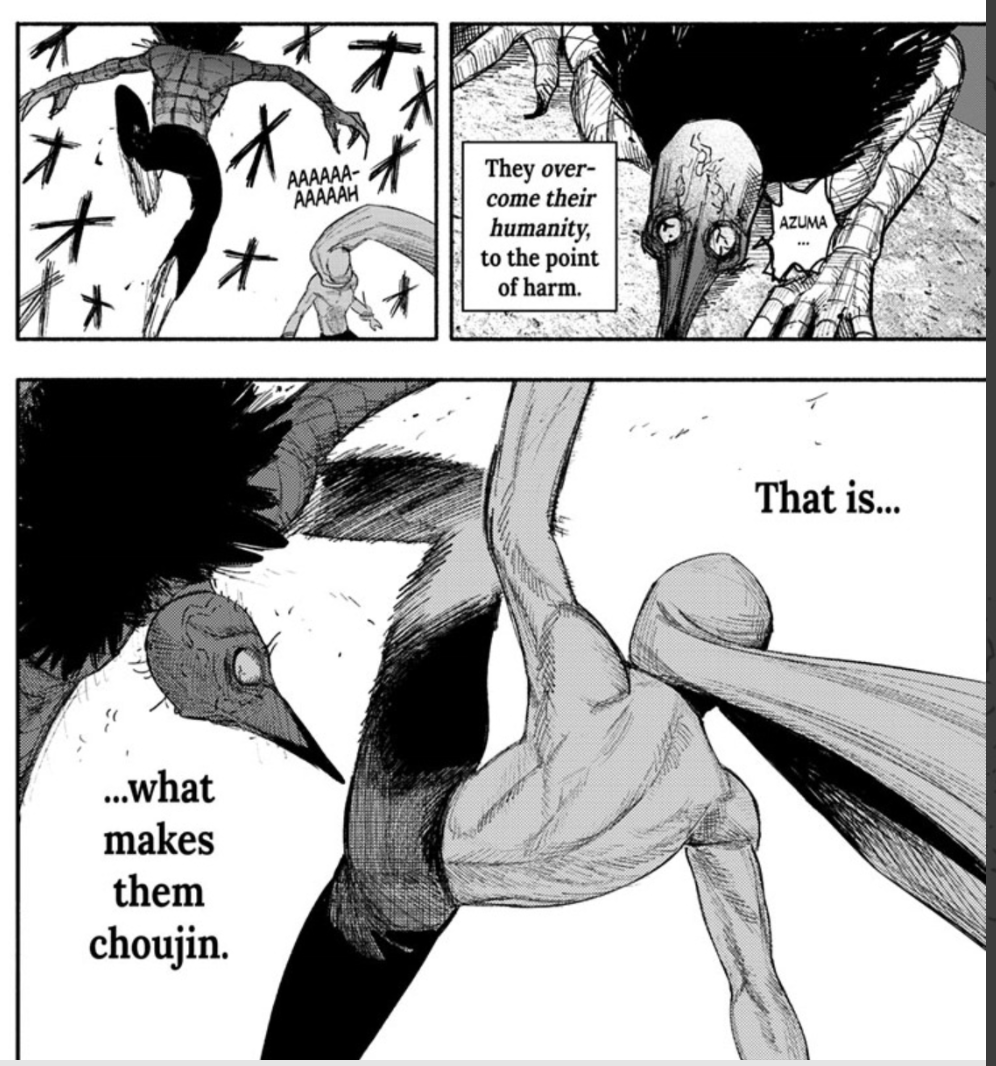

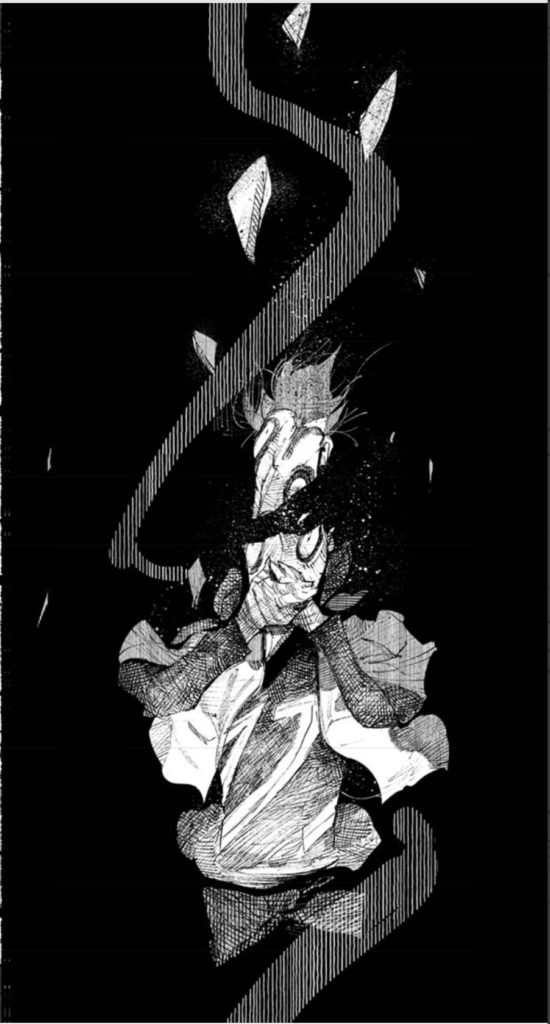

Been reading / thinking about Choujin X and Chainsaw Man, and also Masks (the PbtA superhero game). I had a fun time playing it with my friends, but it felt a little overeager to steer us into the drama stuff and not as interested as I would have liked in the doing cool/gruesome shit (I’m not huge into cape comic stuff, but one of the compelling things to me about it is freakishness, which Masks feels like it shies away from even as it provides it as an option). The thing about mechanizing all of the conflict is that I’m not sure how much the mechanics are actually doing; if somebody is willing to lean into character beats and personal conflict, they’re probably going to do so regardless of how many Moves support it. I do like thespian club high drama bullshit, but I don’t like being led by the nose.

So anyway, I wrote this up with these things in mind: a light mechanical framework for a high-ick superhero-type game in the vein of Choujin X or Chainsaw Man that lets players jump into the genre emulation stuff if they want to. It’s not like…mechanically ingenious, but I suspect it will at least work for a few fun games with my players.

Concept

In the decades after the failed Apocalypse, the broken war machines and defeated soldiers of Heaven and Hell sublimated into the soil and water and air of Earth, leaching even into the bodies and blood of a busily (if miserably) rebuilding humanity. Some lucky few found themselves with influence over the world once reserved for the supernal and infernal: Decrees, the entitlement to govern worldly phenomena dispensed by Heaven to angels before the Fall.

Think: hyperindustrial near-future, an island-metropolis where you can find anything whether your want to or not, superpowered mercenaries who nonetheless have day jobs, the restoration of everyday life after many years of privation and destruction, scientists dissecting angels in government laboratories, smugglers with lead canisters full of demon hearts, old battlefields covered with salt statues of soldiers half-submerged in iridescent slicks of black metal, slowly drifting away from what is familiar and friendly in your life to something dark and unknown but perhaps not entirely undesirable

PCs are once-regular people who found themselves with Decrees living in the Autonomous City San Serafin, built after the Apocalypse and a place where all things converge.

Checks

When you do something difficult, risky, or unpredictable, roll 2d6. If the highest die is a 1-3, you fail. If it’s a 4-5, you succeed at a cost: your goals are only partially achieved, you pay a cost, or suffer a complication. If it’s a 6, you succeed.

You can roll an extra die if on the whole your characteristics and the situation are favorable. You must roll one fewer die if on the whole your characteristics and the situation are unfavorable. If it’s ambiguous, default to 2d6.

Using your Decree is always difficult, risky, or unpredictable.

Characteristics

Pick 2 from each list below. You can’t pick two characteristics in the same row, e.g. being perceptive and oblivious at the same time.

| strong | weak |

| tough | frail |

| quick | slow |

| knowledgeable | ignorant |

| streetwise | naive |

| perceptive | oblivious |

| intimidating | wallflower |

| deceitful | guileless |

| persuasive | unlikable |

| reputable | irreputable |

| wealthy | impoverished |

Pick 1 from the list below.

- Waiter

- construction worker

- burglar

- student

- assassin

- bureaucrat

- farmer

- hacker

- actor

- poet

- journalist

- carpenter

- welder

- doctor

- nurse

- EMT

- painter

Resisting

When you resist something happening to you that you don’t want to happen, make a check like normal.

The GM doesn’t roll; players either avoid adverse situations or make Resist rolls against them.

Damage

By default, you can survive 8 Harm. Default damage you take is 2; it can be reduced to 1 or 0 by resist rolls or increase to 3 or 4 by difficult circumstances and strong enemies.

Similarly, default Harm you cause is 2; it can be reduced to 1 or 0 by tough enemies or increased to 3 or 4 by good plans.

Comebacks

If reduced to 0 Hits, make a Resist check. If you succeed, say something you found out about the nature of your Decree while you were so close to death, and regain half your hits.

If you fail, you’re taken out until your allies can get you to a safe place. If your whole team gets taken out, you wake up in a worse situation.

Divinity

Your Decree gives you power over…

- Scissor

- Mirror

- Paper

- Ink

- Smoke

- Dream

- Snake

- Fox

- Octopus

- Nightingale

- Moth

- Flower

- Shadow

- Ribbon

- Needle

- Moonlight

- Bronze

- Clay

- Memory

- Mirage

Your Decree works by means of…

- Touch

- Incantations

- Gestures

- Agonizing exertions of pure willpower

- Summoned familiars

- Symbols you write

- Your body changing its shape

- Tools, implements, or weapons

- A being that inhabits your body

- Your blood

It is your Decree’s nature to be…

(Roll once to determine a positive nature on the left, then pick any two negative natures that don’t share the row of the positive nature. Your power cannot be swift-acting and slow at the same time, for example).

(These don’t have precise mechanical effects but will come up as you use your powers, especially when you roll failures or partial successes).

| 1 | Swift-acting | slow |

| 2 | Long-lasting | ephemeral |

| 3 | Potent | weak |

| 4 | Precise | uncontrollable |

| 5 | Mercurial | predictable |

| 6 | Sustainable | exhausting |

| 7 | Cooperative | malicious |

| 8 | Respectable | disturbing |

Unfortunately, your power has complicated your everyday life by…

- Permanently altering your body’s shape and/or appearance in some troubling or inconvenient way

- Frightening or angering the people in your life or community

- Attracting the attention of an organization that wants to use your talents for its own ends

- Attracting the special attention of an organization that kills people with your talents

- Requiring you to consume an unusual or illicit substance to survive

- Killing someone significant, either to you personally or society at large, when it manifested

Example

The assumption is that we’re filling in the spaces a little, so if a Decree is NEEDLE and works by means of incantations and is slow and disturbing but potent, you could say that its owner can create needles that break through nearly anything, but they must clearly and precisely describe what they are trying to pierce. If they are gagged or unable to easily breathe, they can’t do anything out of the ordinary, but they could use their decree if bound or blinded.

Missions

Despite your ordinary day-to-day life, you are beholden to the Divinity School to carry out their dangerous business from time to time.

Location

- The Spearyards – industrial district. factories, laboratories, foundries, with substantial abandoned areas

- The Churchyards – historical and district, home to the University

- Campo Greco – rich residential District

- The Old Royal Park – huge park containing a small old-growth forest

- Madrugados – working class residential district

- The Esplanades – government district, as well as museums, theaters, cultural institutions

Duty

- Protect object

- Protect VIP

- Kidnap enemy

- Retrieve object

- Retrieve VIP

- Assassinate enemy

- Destroy object

- Surveil VIP

- Surveil enemy

- Surveil object

Object examples: flash drive of research data, briefcase of cash, demon heart, etc

VIP/ Enemy examples: company president, potential Divinity, ambassador, witness, etc

Rival

- Killy, whose decree is JAW. Disheveled young man with very sharp teeth in an oversized sweater; wears crime scene tape around his neck like a scarf. He can inflict a bite wounds of nearly any size on whatever he touches, and by tracing a line with his finger on something can make a mouth appear on it that bites what he wants and can speak for him if he wills it to.

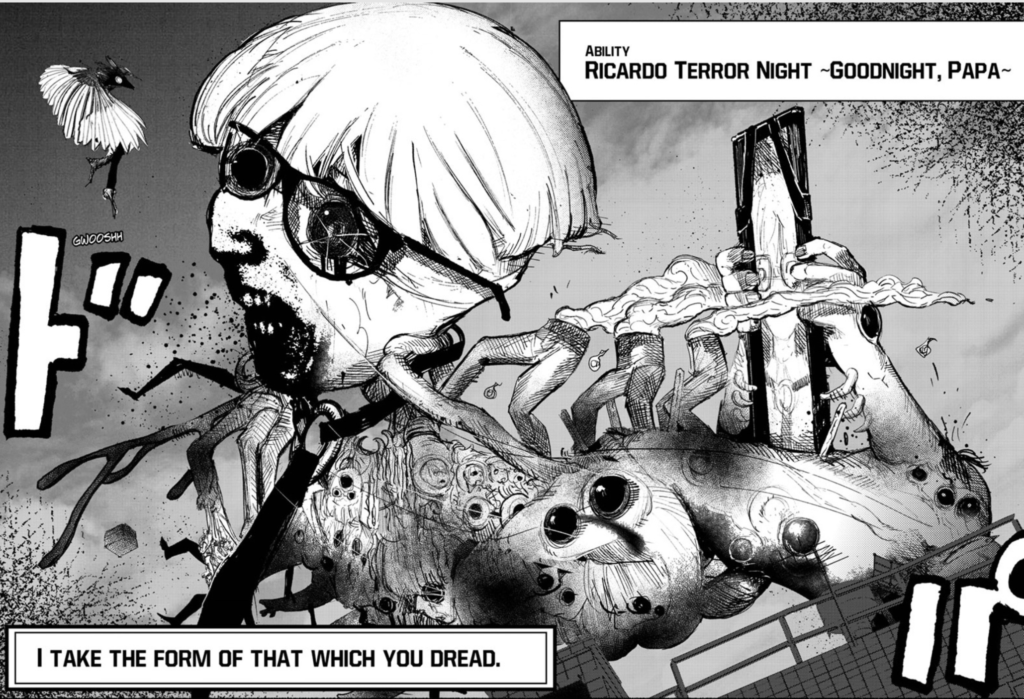

- Traumerai, whose Decree is NIGHTMARE. Wears ruffled pinafores and big ribbon ties and vents monsters out of the gill slits on her temples, which usually take the form of wolfish stuffed animals with pitbull jaws, bat wings, and button eyes.

- Ursula, whose decree is CURSE. Always expressionless, with straight black hair and sensible black clothes. Attended by her familiars, Gog (black-clad, with a white mask) and Magog (white clad, with a black mask). If someone hears a condition stated by Gog and a consequence stated by Magog, it will come true for them and remain true indefinitely or the terms of the curse are met.

- Bellamy, whose Decree is NIGHTJAR. A sensible and politely brutal middle-aged man who dresses in suits and ties. Fights with incomprehensible speed and allegedly drinks blood.

Complication

- The job involves overcoming inordinately intense security

- The job involves infiltrating a high society event

- The job must not attract the attention of the general public

- The job must be done in a very short amount of time

- The job involves some serious law-breaking

- Multiple Divinities will be working to stop you

Advancement

When you have encountered three more reasons to become more than what you are such as encountering the true nature of your power while on the cusp of death, eating a demon heart, defeating an enemy who vastly outmatched you, making a true friendship, or radically changing the way you see the world under doubt and duress, you gain a Raise.

A Raise lets you use your Decree to do something truly marvelous and grotesque: become an unstoppable monster, summon a god-slaying spear from the heavens, banish a city block to the Moon, whatever. You don’t need to roll to make it happen or do what you want, but it does have to be an outrageous display of power. You can use a Raise at any time, though doing so wantonly may attract hostile attention.

When you use a Raise, at the end of the session, talk with the GM and the other players about how your character has changed, and how they can use their Decree in ways they previously did not know were possible.

After the first Raise, it takes four reasons, after the second it takes five, and so on.